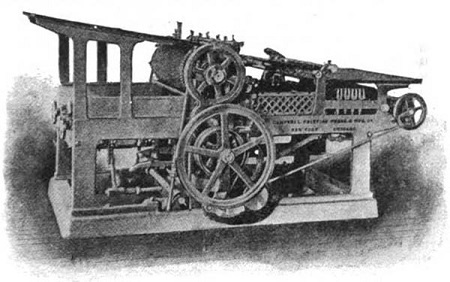

I have returned to the long journey of restoring, or resurrecting, a beautiful piece of antique printing machinery, the Campbell “Century Pony” flatbed cylinder press. It is a two-revolution press which, unlike the larger “drum cylinder” presses, uses a smaller cylinder that makes two revolutions for each impression on the horizontal bed that moves back and forth underneath. On the bed’s return under the cylinder, impression is avoided by a slight upward movement of the cylinder.

The Campbell Century Pony presses were a great success and were made between 1895 and 1906, being developed out of Campbell’s earlier “Economic” model. My Campbell came with a counter that was dated 1897. This could be a good clue as to its production year. Moreover, during the life-span of a press’s production the number produced is usually weighted toward the beginning. (Yearly production numbers usually tailed off sharply in the final years.) The “Century” was marketed to the approaching new century, and most of the advertisements are seen in the mid-to-late 90s. For example, a picture in an article of 1896 depicts my press very accurately (From Printer’s Ink, Vol. 18):

The article states that the press weighs over 8600 pounds and is valued at $1600 – a pretty penny back then! One online source states that the average wage earner in 1890 made $1.53 a day and worked 279 days a year, thus making about $480 for the year. The Campbell was thus 3.33 years of wages for the average worker of the time. A low wage today ($10 / hr), at 5 days a week for 52 weeks gets you about $20,800 for the year. We might say that the Campbell would be valued at $70,000 in today’s dollars. It’s a high-end “19th century flatbed cylinder press” in design and spirit, which was a major purchase for any upstart printer that took decades of hard work to pay off. One question lingered for me: where was it born?

Where the Campbell Was Built

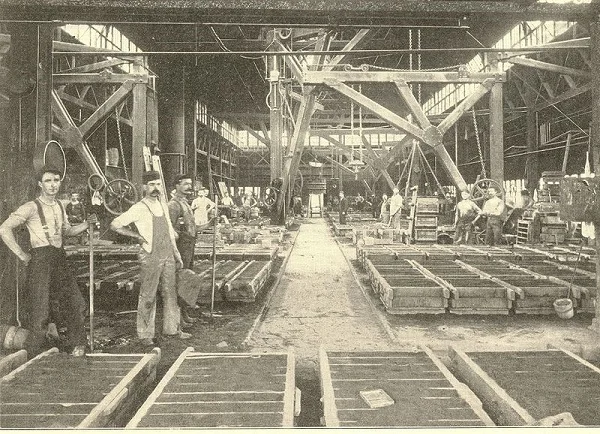

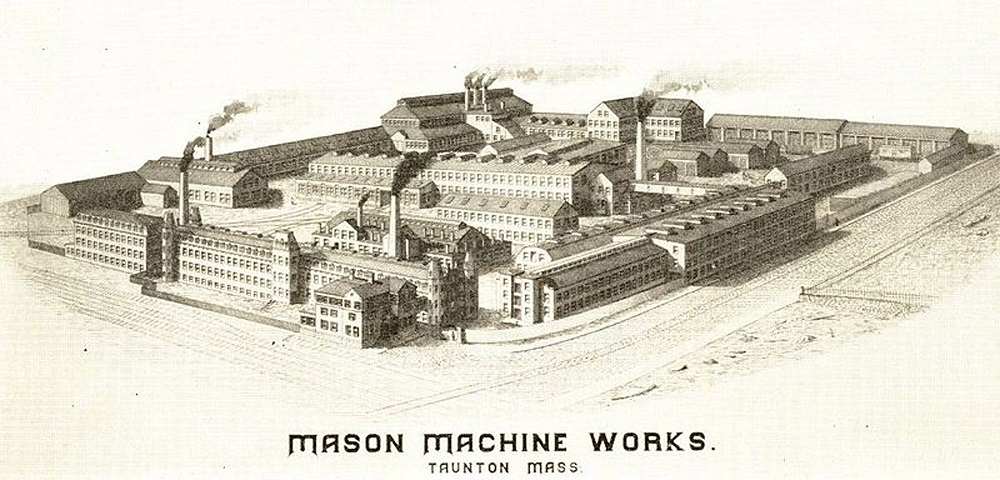

A little research reveals that the Campbell Printing Press and Manufacturing Company originally built its own presses in Brooklyn but in 1879 the patent owners contracted with Mason Machine Works in Taunton, Massachusetts, to build the presses. It was a windfall for that company, and they expanded their operations. By 1893 some 950 people were employed.

A 1904 article in the Iron Age, Vol. 74, proves that Mason Machine works was still building the presses in 1904. Consequently, it’s almost completely certain that my Campbell was forged and built in this facility in Taunton, Massachusetts:

This is from an 1899 publication of the company. Shipping of presses west probably routed through Illinois. More research in Leadville might uncover its arrival and presence there. I wonder how and when my Campbell press made it to Colorado. There are several scenarios. It may have shipped new to the printing operation in Leadville, sometime between 1895 and 1906. It may have begun its work in some other town, and was purchased used at some later date. It went from Leadville to Arvada in the 1970s, where Mr Stoddardt used it to print posters for Lakeside Amusement Park. It supposedly hadn’t been run for 20 years by the time I heard of it in 2010. It was moved to my shop in Fort Collins in March, 2011. Two weeks ago I inked up the press and flawlessly hand fed 20 newsprint sheets for a letterpress poster through the press. It took one minute, running at 1200 impressions per hour.